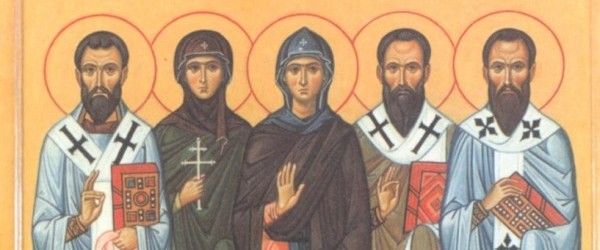

ST. MACRINA

Story of Macrina, written by her brother Gregory of Nyssa.

“I am sure you do not forget our meeting, when, on my way to Jerusalem in pursuance of a vow, in order to sec the relics of the Lord’s sojourning in the flesh on the actual spots, I ran across you in the city of Antioch; and you must remember all the different talks we enjoyed, for it was not likely that our meeting would be a silent one, when your wit provided so many subjects for conversation.

“As often happens at such times, the talk flowed on until we came to discuss the life of some famous person. In this case it was a woman who provided us with our subject; if indeed she should be styled woman, for I do not know whether it is fitting to designate her by her sex, who so surpassed her sex. Our account of her was not based on the narrative of others, but our talk was an accurate description of what we had learned by personal experience, nor did it need to be authenticated by strangers.

Nor even was the virgin referred to unknown to our family circle, to make it necessary to learn the wonders of her life through others, but she came from the same parents as ourselves, being, so to speak, an offering of first-fruits, since she was the earliest born of my mother’s womb. As then you have decided that the story of her noble career is worth telling, to prevent such a life being unknown to our time, and the record of a woman who raised herself by “philosophy” to the greatest height of human virtue passing into the shades of useless oblivion, I thought it well to obey you, and in a few words, as best I can, to tell her story in unstudied and simple style. The virgin’s name was Macrina…[continued]

SOURCE: TERTULLIAN.ORG

ST. EMMELIA

Macrina’s mother, Emmelia, had a very interesting life as well. It stands to reason that her children were impacted by her faith. Most of what we know about her comes from the above letter from Gregory to his friend regarding Emmelia’s daughter Macrina.

ST. BASIL THE GREAT

Basil the Great, the son of St. Emmelia and St. Basil, was a scholar in Cappadocia. He is considered as one of the Three Hierarchs of the Orthodox church, along with Gregory of Nazianzus and John Chrysostom.

Here’s a great excerpt from a writing of Gregory of Nazianzus wrote, documenting what Basil had to go against when Emperor Valens sent his prefect Modestus to try to force Basil to bow to the gods of Rome:

“What do you mean, you, sir, [Modestus] said, adding his name, for he did not yet deign to call him bishop, “by daring to resist so great a power, and by being the only one to speak out with arrogance?”

“In what respect,” replied our champion, “and what is this madness you speak of? I do not yet understand.”

“Because you do not honor the religion of your sovereign,” he said, “when all others have given way and submitted.”

“I do not,” said Basil, “for this is not the will of my true Sovereign, and I cannot bring myself to worship a creature, as I am a creature of God and bidden to be a god.”

“But we, what are we in your eyes? Or are we nothing?” said the prefect, “who give you these commands? Besides, is it not a great thing for you to be ranged with us and have us as your associates?”

“You are indeed prefects,” said Basil, “and illustrious, I will not deny it, but in no way more honorable than God. To be associated with you is a great thing, certainly. You also are creatures of God. But I would be associated with you as with any of my subjects. Faith, not the person, is the characteristic mark of Christianity”.

Then the prefect became excited and seethed all the more with rage. He rose from his seat and addressed Basil in harsher tones. “What,” he said, “are you not afraid of my authority?”

“Afraid of what? What could I suffer?”

“Any one of the many punishments which lie within my power.”

“What are these? Make them known to me.”

“Confiscation, exile, torture, death.”

“If there is anything else,” said Basil, “threaten me with that, too, for none of these you mentioned can affect me.”

The prefect said to him: “How can that be true?”

“Because, said Basil, “the man who possesses nothing is not liable to confiscation, unless you want, perhaps, these tattered rags, and a few books, which represent all my possessions. As for exile, I do not know what it is, since I am not circumscribed by any place, nor do I count as my own the land where I now dwell or any land into which I may be cast. Rather, all belongs to God, whose passing guest I am. And as for torture, how can they rack a body that exists no longer, unless you refer to the first stroke, for of this alone you are the master? Death will be a benefit, for it will send me to God sooner. For Him I live and order my life, and for the most part have died, and to Him I have long been hastening.

These words astounded the prefect.

“No one,” he said, “up to this day has ever spoken in such a manner and with such boldness to me,”

“Perhaps you have never met a bishop,” said Basil, “or he would have spoken in exactly the same way, having the same interests to defend.”

The Fathers of the Church, Gregory Nazianzus

ST. JOHN CHRYSOSTOM

The “Teacher of Antioch” was given the moniker Chrysostom “Golden-tongue” because of his abilities in speech. According to Philip Schaff, “Chrysostom was one of those rare men who combine greatness and goodness, genius and piety, and continue to exercise by their writings and example a happy influence upon the Christian church. He was a man for his time and for all times.”

Philip Schaff, in his edit of Chrysostom’s work, quotes church historians Ruess and Farrar. Ruess pays this tribute to Chrysostom “The Christian people of ancient times never enjoyed richer instruction out of the Bible than from the golden mouth of a genuine and thoroughly equipped biblical preacher.” Farrar calls Chrysostom “The ablest of Christian homilists and one of the best Christian men,” and “the bright consummate flower of the school of Antioch.” However, on the other side, Martin Luther called him a “rhetorician full of words and empty of matter.”

Of all the early church fathers, his sermons are some the most readily and numerously found. He wrote in Greek, so some of his earlier works are not available online. Christian Classics Etherial has many of his works available for download or online reading.

The Teacher’s views on RELICS, as debated in Trunk of Scrolls, was significant in the later councils, in particular the Second Ephesus Council, which officially took a stand on the miracle-power of relics. His “Against the Opponents of Monasticism” mentions the hoodlums of Antioch, and the harm they pose to young men. This is the source of the fictional situation that happened to Marcellus in Trunk of Scrolls.

St. SIMEON THE STYLITE (THE YOUNGER)

The story of Simeon presented in Trunk of Scrolls accurately reflects the legend surrounding Simeon. He was a boy from Antioch, who tamed a wildcat at a tender age and lost his first tooth while a stylite next to John the Stylite in the Admirable Mountains. Here are two websites that give detail into his life and legend.

St. Simeon the Elder

Simeon’s namesake, a Simeon Stylites the Elder of Syria, was active in the theological debates during Chalcedon Council, though he was on the Monophysite side.

These letters of the Simeon the Elder, and this academic paper from UC Santa Barbara shows the involvement of the first Stylite in the councils.